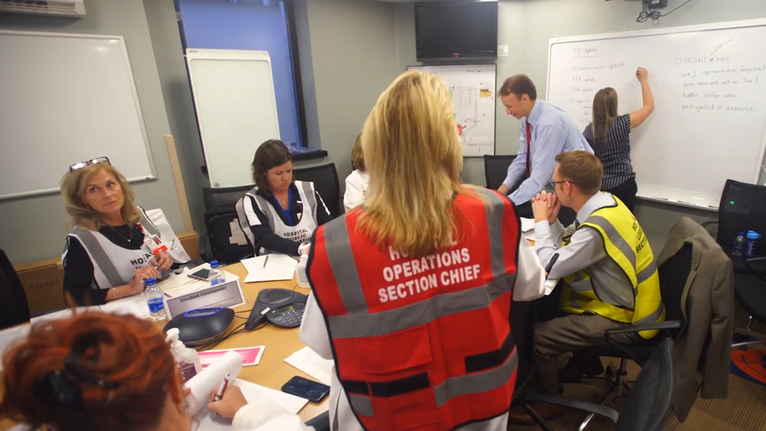

10:23 a.m. — UC Medical Center Command Center: The hospital incident command team, led by Meg Lewis, MSN, RN, associate chief nursing officer at UC Medical Center, gather inside the hospital’s packed command center to prepare for a 10:30 a.m. conference call with other team leaders. The call includes leaders from operations, communications, logistics, air care/mobile care, trauma, operating room and others.

The incident command team collaborates together in a secure, private space during and after a regional emergency. Their objective is to lead the system through an emergency response and plan how each UC Health facility will handle the huge number of incoming patients.

“We have a great team. We prepare like this all the time, and practice makes us even better,” Meg said.

Members of the capacity management team monitor patient statuses and bed availability, while other site commanders are communicating traffic updates, supply availability and internal messaging for employees.

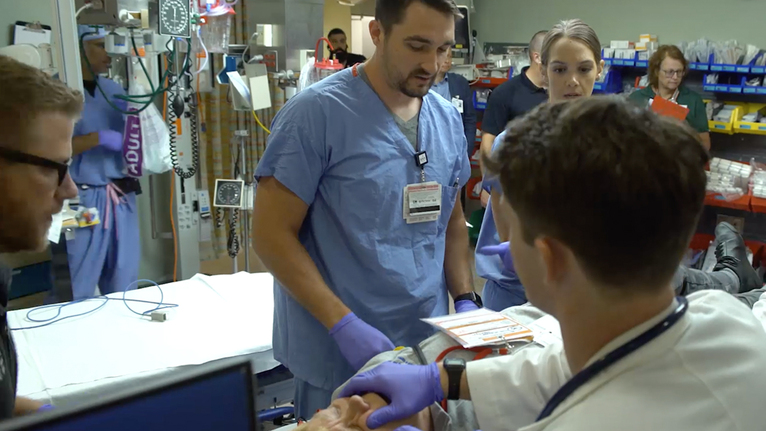

10:41 a.m. — UC Medical Center: Dr. Curry continues to oversee the flow of patients through the Emergency Department, saving precious resources for the most critical patients. A staff member alerts him of another incoming patient: “I’ve got another patient coming in with blunt chest trauma.”

Dr. Curry asks, “Is she stable?”

“Yes.”

“She’s going to have to wait.”

After a mass casualty, space is one of those “pinch points.”

“Unfortunately, someone that might go to the operating room right now on a normal day when we have plenty of space might have to wait until the case in front of them is done,” Dr. Curry said.

11:15 a.m. — Command Center: The incident command team holds a second debrief.

Around 90–100 victims now have arrived at UC Medical Center, with 14 in the operating room. The hospital still has 11 operating rooms available. UC Health’s West Chester Hospital received 14 patients and can accept 49 more. Daniel Drake Center for Post-Acute Care is prepared to receive up to 20 victims.

Meanwhile, UC Health Public Safety officers manage foot and vehicle traffic from members of the news media around campus. Updates are given about where family members can reunite with victims.

The command center closes following the call, ending the simulation.

12:00 p.m. — UC Gardner Neuroscience Institute Building: A “hotwash,” or an evaluation after an emergency exercise or training session, takes place.

As one of the key leaders of the drill, Maria Friday, director of Emergency Management at UC Health, applauds the teamwork from everyone who participated.

“I’ve been here for about six years, and this is the most attended exercise with a lot of involvement and a lot of different departments—from physicians to environmental service staff to administrative staff,” said Maria. “The collaboration and teamwork was fantastic.”

Maria’s background prepared her to lead drills like this. She holds a master’s degree in healthcare emergency management from Boston University, one of the few colleges in the nation to have this unique program. Her goal is that UC Health keeps up the momentum going forward by continuing to work with the community to prepare for these drills.