How it Works

The amniotic membrane acts like a supportive “scaffold” that gives the patient’s own tissue a framework to heal. It also releases natural healing signals that reduce inflammation and encourage repair. This combination of support and signaling can help wounds recover more effectively, especially those that have resisted other treatments.

While amniotic membranes are already used in other fields — such as treating diabetic ulcers, orthopedic injuries, and in reconstructive and eye surgery — this is the first known application worldwide for treating VAD-related infections.

Where Does the Amniotic Membrane Come From?

The amniotic membrane used in this case (Clarix 1K®) is donated by consenting healthy mothers after traditional (vaginal) or scheduled Cesarean (C-section) births within the U.S. All donors undergo rigorous social, physical, and medical screening to ensure safety and tissue suitability. You can learn more at Biotissue’s website.

Not all hospitals offer placenta donation. Availability depends on whether a hospital is partnered with accredited tissue banks, has the right infrastructure in place, and secures informed consent from the mother. It is not automatic at every birth, but many hospitals across the country now offer the option.

Is This a Common Medical Practice?

Using placental tissue in medicine is well established in some specialties and expanding into others. For example, amniotic membranes are commonly used in:

- Ophthalmology: for eye surface reconstruction (e.g., Prokera®, AmnioGraft®)

- Orthopedics and wound care: for soft tissue repair, tendon and nerve reconstruction, trauma, and joint replacement

- Reconstructive surgery: for chronic or difficult wounds

Thanks to modern cryopreservation methods (such as CryoTek® technology), these tissues can be preserved while maintaining their healing properties, making their use increasingly widespread across regenerative medicine. Until now, however, there had been no reported use in treating VAD-related infections.

Why This Matters

VAD infections remain one of the most challenging complications in advanced heart failure care. Depending on the device and duration of follow-up, infection rates range from 13–17% within the first year to 24–34% over longer follow-up periods. Many single-center studies report about 20–25% of patients experiencing driveline infections over time. Despite advances in prevention, infections remain common — and some go undiagnosed.

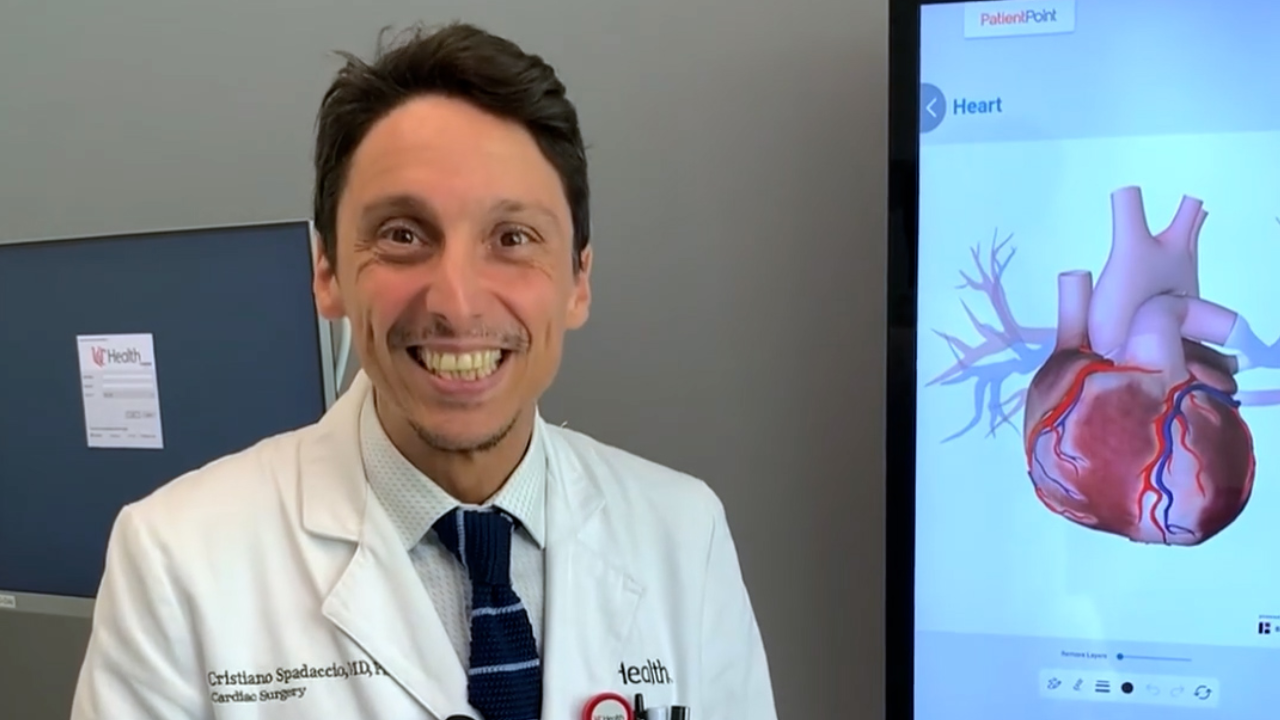

“Persistent driveline infections remain among the most difficult challenges in advanced heart failure care. This first-in-the-world case not only offers new hope for patients who have exhausted conventional options but also demonstrates how regenerative strategies can become a valuable adjunct and a therapeutic weapon in the armamentarium of cardiovascular surgery and medicine. Here at UC Health, we are fortunate to have advanced laboratory research efforts in this field and proud to have made the pioneering step of translating them into the clinical setting, and so to move regenerative medicine from concept to patient care," says Dr. Spadaccio.

This world-first success by Dr. Spadaccio and the cardiac surgery team not only offers hope for patients facing these persistent infections but also highlights how cross-disciplinary innovation can push medicine forward.

Congratulations to Dr. Spadaccio and the entire cardiac surgery team for achieving this milestone and shaping the future of advanced heart care.