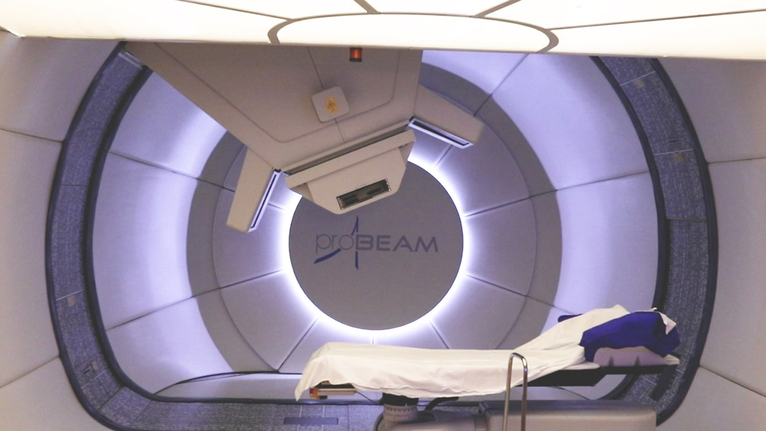

In a locked room in West Chester, Ohio, a 90-ton machine accelerates millions of proton particles.

These particles zoom and turn through a tube and out of a beam nozzle inside a patient treatment room.

Within seconds, the particles enter a human body. This beam of protons stops, with millimeter precision, on a bundle of tumor cells.

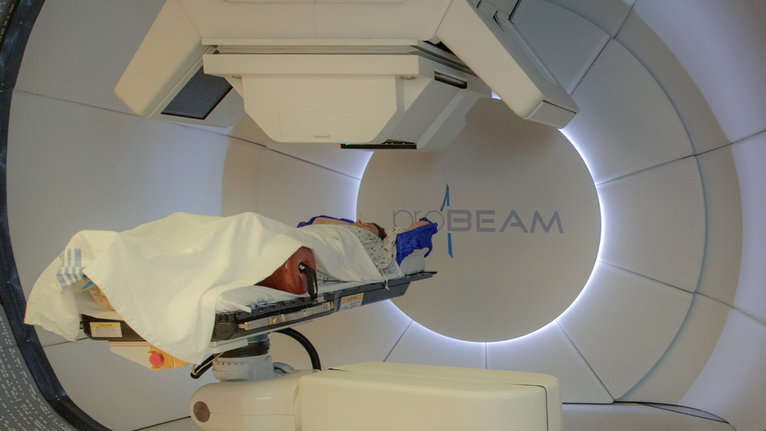

But the man lying on the table in a proton therapy gantry receiving this form of cancer treatment can’t tell the difference. This form of therapy doesn’t hurt; there’s no visible beam of light; and the radiation itself makes no sound.

Instead, he rests under a blanket, eyes closed, hands under his head.

Soft acoustic music still plays from the last patient’s treatment. One of the radiation therapists switches to a song that better suits this patient’s tastes—Journey’s “Any Way You Want It.”

Now he waits, as proton particles work to destroy the cancerous cells in his body so that they can no longer divide and multiply. The healthy cells that surround the cancerous ones are mostly spared.