Optimal Management of Patients Surviving an Out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest

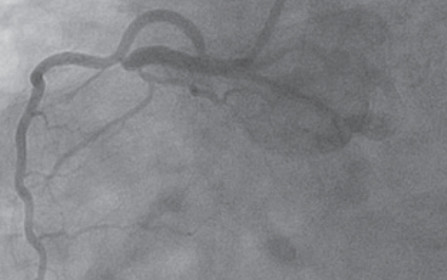

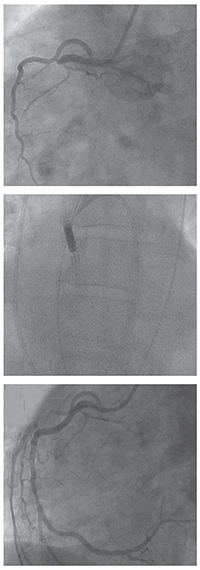

(From top to bottom): A “culprit” lesion in the proximal right coronary artery, post intervention result, and left ventricle placement of the Impella mechanical circulatory assist device to sustain cardiac output.

Patients who suffer cardiac arrests outside of hospitals generally die. Mortality is 90%, according to 2013 data reported by the American Heart Association (AHA).1

There may be hope. The University of Cincinnati Medical Center, and several medical centers in the United States, have established collaborative interventional teams, including 24-hour cardiovascular and neurologic intensive care units to work in concert to improve survival for arrest patients.

According to Timothy Smith, MD, of the University of Cincinnati Medical Center Heart, Lung, and Vascular Institute, “Management of out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) requires coordinated care from cardiology, neurology and critical care specialties. It also requires very close collaboration with community fire departments and emergency medical services, so they are able to rapidly recognize OHCA, begin resuscitation and within minutes, get the patient to a center that has a standing team ready to respond.” Christopher Miller, MD, medical director of Emergency Medicine adds, “Our prehospital partners are the vital first and second links in the chain that leads to successful OHCA outcomes.”

Optimal outcomes are seen when return of spontaneous circulation is within 15 minutes after the start of resuscitation. Arthur Pancioli, MD, FACEP, professor and chair of the department of emergency medicine, notes, “The Emergency Medicine physicians at University of Cincinnati Medical Center provide more prehospital care education and training than any other group in the region and the division of Prehospital Care provides oversight and direction for the majority of the ambulance runs in the region.” Miller explains, “Management of a patient who sustains OHCA is not just a medical challenge; it requires [sophisticated] coordination of multi-disciplinary logistics. It’s really our combined team efforts that provide our patients the best chance at survival.”

In 2014, the University of Cincinnati Medical Center handled 101 patients with OHCA. Based on AHA recommendations2 and current data3,4, key issues in managing these patients are preserving neurological function, and performing early cardiac interventions. Smith explains, “Here, OHCA patients are usually immediately cooled. They undergo induced hypothermia, where body temperature is lowered to 36°C; this may improve their chances for a better neurological outcome.”

William A. Knight IV, MD, FACEP, Associate Professor, Emergency Medicine and Neurosurgery, adds, “We often initiate temperature management or cooling in the ED and follow the patient throughout their hospital course, regardless of what ICU they are triaged to.” Knight also emphasizes the importance of EEG monitoring in OHCA cases, to diagnose and initiate treatment of post-cardiac arrest seizures, which occur in up to 20% of patients.

Patients with clear evidence of a myocardial infarction are routed immediately to the catheterization lab to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to open blocked coronary arteries. Smith adds, “We typically initiate PCI in appropriate patients,” in line with the 2010 AHA Guidelines for CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care5 which state “coma and the use of induced hypothermia are not contraindications or reasons to delay PCI…[and] PCI after [return of spontaneous circulation] in subjects with arrest of presumed cardiac etiology may be reasonable, even in the absence of a clearly defined ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).” Cooling and PCI may also be performed concomitantly. Large case series reports2,3 seem to indicate that early and successful PCI is associated with improved odds of survival for most patients with OHCA. Other positive prognostic signs include: time from collapse to basic life support less than five minutes; non-diabetic; age less than 59 years; initial rhythm marked by ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation; and presence of ST elevation. Additional tools such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and ventricular assist devices, can serve as what Smith refers to as “a bridge to decision,” supporting the patient while longer-term treatments are considered or prepared.

Beginning with prompt resuscitation in the community, and continuing through coordinated care in the ER and hospital, there is now emerging hope for patients with OHCA.

Timothy Smith, MD

Timothy Smith, MD

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Cardiovascular and Critical Care Medicine

(513) 558-6804

smith5ty@ucmail.uc.edu